Le Declic, 1987, Amiga. An untranslated Italian erotic visual novel.

The Western Visual Novels of the 1980s

Zorkquest: The Crystal of Doom by Infocom

Infocom's

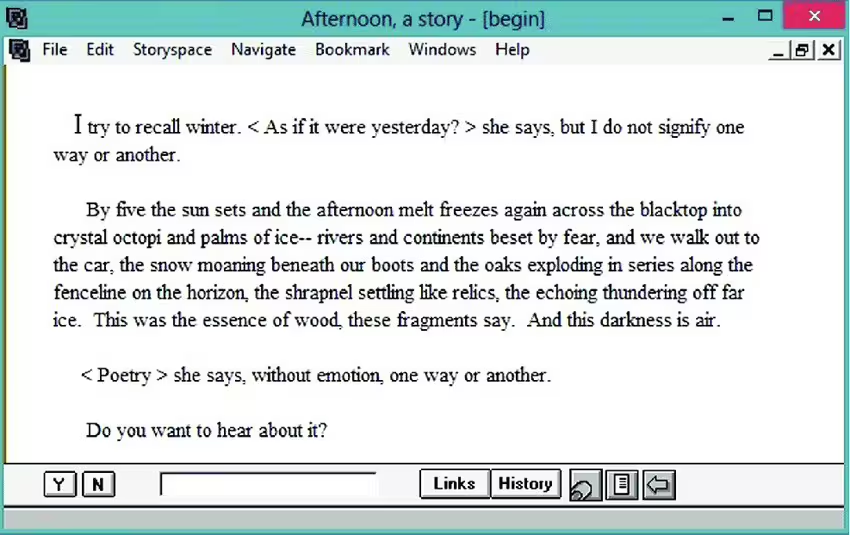

Hypertexts are the technical predecessors of modern Twine games and the primary thing which separates them from early narrative video games is the cultural place from which they emerged. The Infocomics are unpretentious genre works by an acclaimed game developer, where the most famous hypertexts were literary fiction coming from established authors and academics. Had Micheal Joyce been published by Electronic Arts instead of Eastgate, I'm confident we'd be discussing his work as a part of gaming, rather than literary, history.

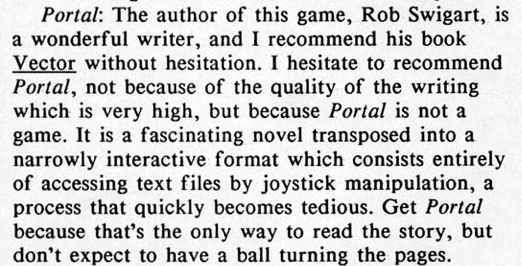

Portal is a prime example of this phenomena. It was written by Rob Swigart, an author and early member of the Electronic Literature Foundation. Released by Activision in 1986 for the Amiga, PC, Commodore 64, Apple II, and Macintosh it is, unlike Swigart's later digital fiction, widely remembered as a video game, with an an entry on Backloggd and everything! Swigart himself, states that it is "in no way a game", but being published by Activision for "gaming computers" like the Commodore 64 has cemented its legacy in gaming history as one of the first (and best) of the Western visual novels. It's worth noting, however, that the gaming press of the time was frequently critical of its lack of interactivity, even while they praised the quality of its writing. Like Automata UK's Deus Ex Machina before it, any praise it received for its artistic achievements was tempered by this insistence that it was "not a game" but you would be hard-pressed to find anyone aware of it today who doesn't consider it to be a game. Even hypertext curators call Portal a game now! It's fascinating how definitions shift over time.

Ursula K. Le Guin, from the introduction to Left Hand of Darkness.

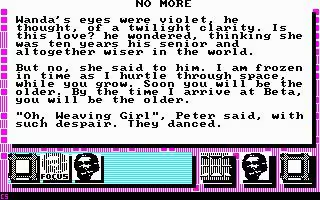

Portal touches on themes of digital age social alienation, the contradictions of utopian idealism, the nature of art, gender identity, dreams, and Carl Jung's collective unconscious. It draws from the Chinese folk tale of the cowherd and the weaver girl and occasionally leaves its New Wave-tinged sci-fi behind for hypnagogic fantasy reminiscent of Lord Dunsany. The protagonists, Peter and Wander, communicate telepathically with one another through their dreams, united across the stars by their shared loneliness. Wanda is cryogenically frozen but aware, sent hurtling through space to an alien star while Peter struggles with the ennui of life in a failing and ambiguous utopia. Their conversations take place in an expressionistic fantasy world, a Jungian tower in which Wanda is imprisoned, as the straightforward prose we've become accustomed to melts into poetry to reflect the unreality of their meeting. The formal characteristics of the work are integral to its narrative; Swigart blends a number of disparate styles to convey the experiential difference between the digital, the physical, and the ethereal.

The dream sequences are a little looser with their formal grammar than the rest of the story, heightening the sense of unreality.

There were "visual novels" made outside America, too, of course. Jaroslav Svelch's excellent Gaming the Iron Curtain discusses the game development scene in communist Czechoslovakia against the backdrop of the failing Soviet bloc of the late 1980s. While official hardware couldn't legally cross the Iron Curtain, clones of popular computers like the ZX Spectrum were available (though uncommon) in the region and many of the games produced for them were translated and made available by the Slovak Game Developer's Association a few years ago. I'd highly recommend reading their history and trying some of them out, it's a fascinating and criminally under-discussed part of gaming history. While many of them have some resemblance to mainstream Western titles (particularly from Spain and Britain given their primary computer of choice), many of the games feature highly idiosyncratic gameplay and narratives. Naturally, due to the young age of their creators, some of the social commentary in these games may come off as sardonic, crude, or nihilistic but another word for that all of that might be "honest." It's unfiltered and raw, the product of young minds that simply wanted to unburden themselves, unconcerned with finding the perfect turn of phrase to express their discontent towards a repressive and socially conservative government that could no longer offer even the illusion of stability.

"Fuksoft" from 1987.

There were many games in the 80s that were much more socially conscious than the popular histories would have you believe, and this is especially true for games whose cultural origins lie outside the global north. Coktel Vision's Mewilo (1987) is a somewhat more traditional adventure game than anything else in this post, but it warrants a mention regardless due to its extreme focus on narrative and its incredible thematic ambition. Though published in France by a French software house, it is primarily the brainchild of two Martinicians: director Muriel Tramis and writer Patrick Chamoiseau, a celebrated Creolite novelist and essayist. Mewilo is a magical-realist mystery game in which you play as a parapsychologist investigating a zombie haunting in St. Pierre the day before it was destroyed by the sudden eruption of Mount Pelée. Drawing from the Carribbean Jars of Gold myth (in which white slaveowners were said to bury their treasure alongside their most loyal slave so that their zombie would be forced to protect it), Mewilo<.i> acts as a portrait into the life and culture of the people of Martinique and is written in a simplified form of Antillean Creole (with a translation cipher included in the manual for people who only speak European French). It also comes with a recipe for calalou and a cassette of Martinician music, and one of the first puzzles in the game involves a quiz about Martinique's culture and history! A veritable honkey filter which includes several questions which directly critique the European imperialists who have colonised them. It is most likely the earliest example of a postcolonial story in the history of video games; a defiant expression of self-determination from the perspective of the colonised in which the very language in which it is written has narrative and thematic importance. And it came out in 1987, the same year that Mega Man was released. It is a beautiful homage to Martinique and its people and would be followed up a year later by the furious cinematic strategy/management/RPG Freedom: Rebels in the Darkness. While only debatably within the purview of this article, I simply couldn't leave it out.

Thematically similar, but somewhat less successful and authentic is Passengers of the Wind, released in 1986 by Infogrammes for the Amstrad CPC, Atari ST, MSX, Amiga, Commodore 64, and PC. It's based on a popular French comic by Francois Bourgeon and is an adventure-romance story (or, if you prefer, a romance in both its most traditional form) which takes place just before the French revolution. Like many modern kinetic visual novels, it's only truly interactive during its occasional decision points which lead you to bad ends and force a reload should you choose incorrectly. The narrative doesn't meaningfully branch nor are there really any puzzles, it is utterly divorced from the conventional adventure game style of the time period. The interface is really quite frustrating, though, and it's not always clear when you've run into a bad end as a result. The translation also leaves a lot to be desired, with its awkward, stilted dialogue that seems, at times, to be lacking vital context. As a result, the original comic is much better way to experience this story. Still, it's an interesting early look at a 'game' for which traditional gameplay was a tertiary concern, a true forerunner of the modern visual novel from a country that few associate with the form and an example of a fascinating period of French gaming history.

But, if I were going to recommend you a politically charged French adventure game that isn't Mewilo, I'm much more likely to point you towards Froggy Software's La femme qui ne supportait pas les ordinateurs (lit. "The woman who couldn't stand computers"), a 1986 game which takes place on the Calvados network and casts you in the role of a woman facing sexual harrassment from an online community. It's not graphical enough to be a visual novel, but it's worth a look all the same, provided you can read French.

Possibly the greatest box art of all time.